Transversus Abdominis

-

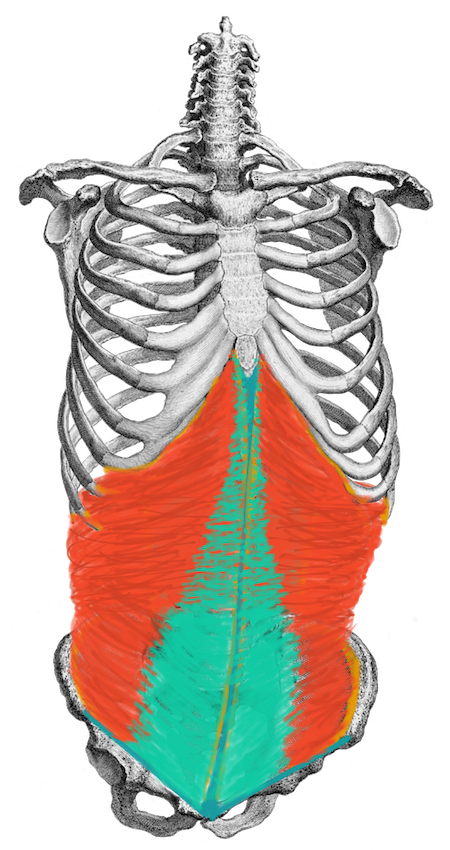

Need to Exhale? Let's talk about the transversus abdominis, the innermost layer of the abdominals*. It plays a key role in the singer's well-organized exhale.

*Today's muscles will be modeled by this beautiful torso skeleton from William Cheselden's 1733 Osteographia. The muscles and connective tissue additions are a product of my own, much more limited drawing skills. As always when studying anatomy, I encourage you to look at as many sources as possible.

-

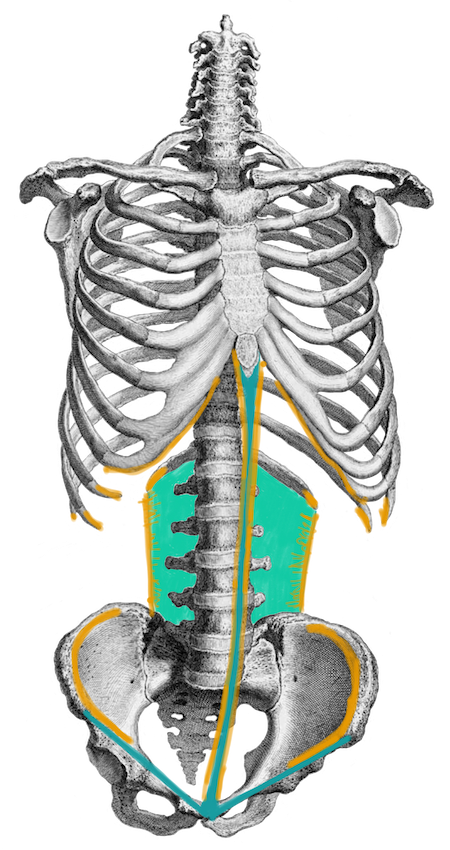

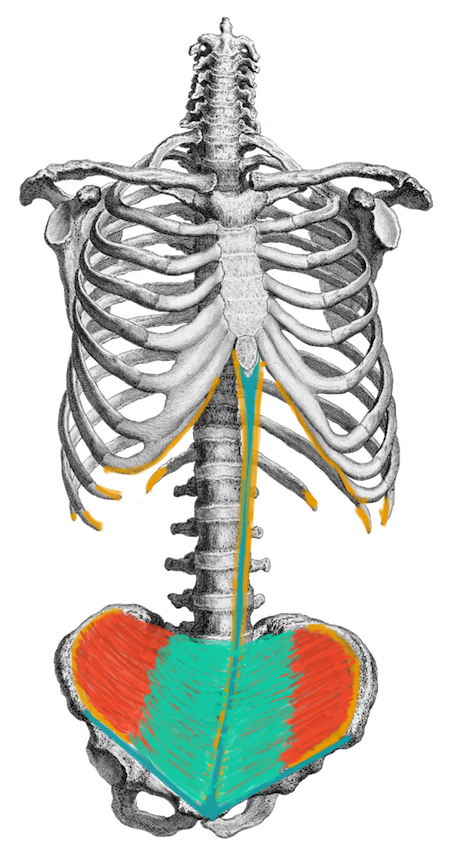

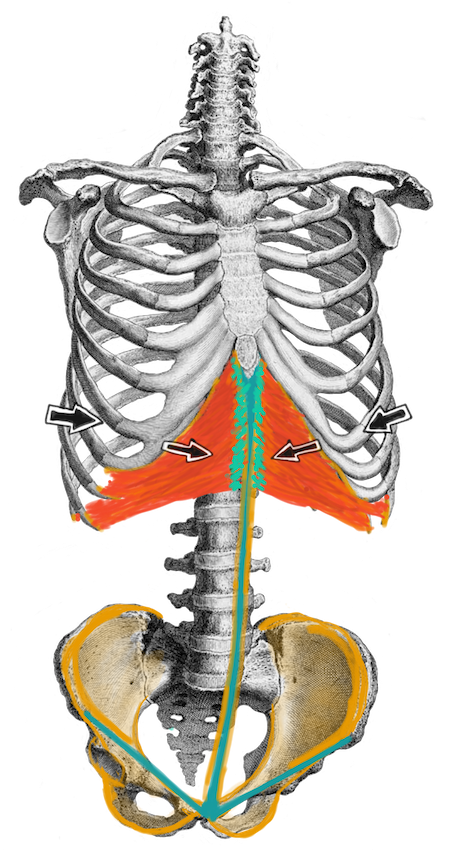

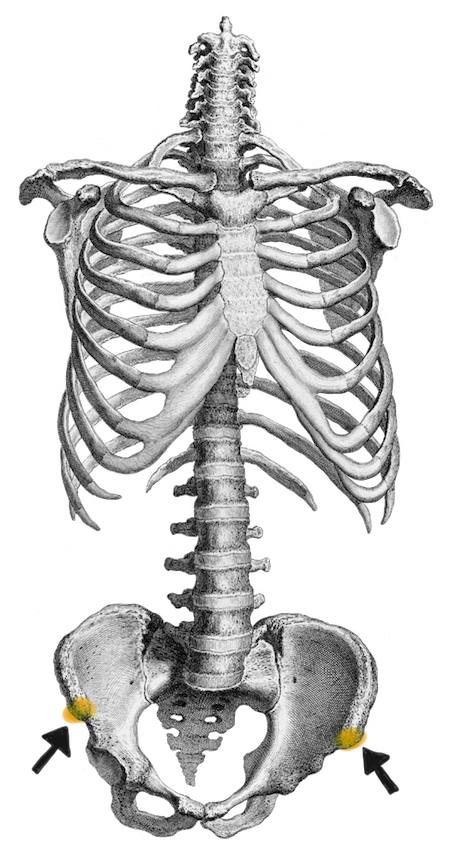

First, let's understand the muscle's location and attachments. We'll start by adding some key connective tissue structures to our skeleton.

- thoracolumbar fascia

-

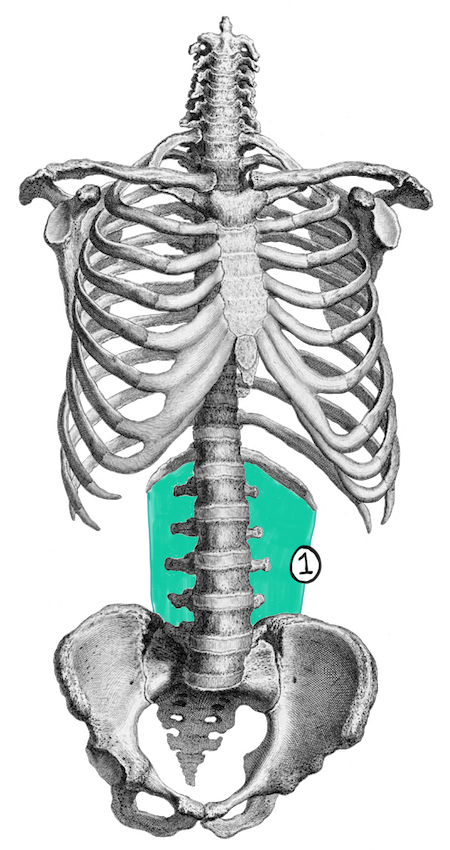

First, let's understand the muscle's location and attachments. We'll start by adding some key connective tissue structures to our skeleton.

- thoracolumbar fascia

- inguinal ligament

-

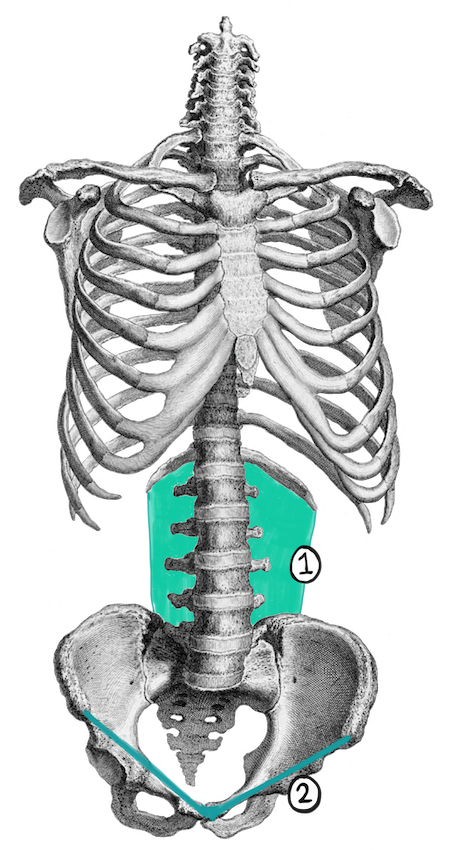

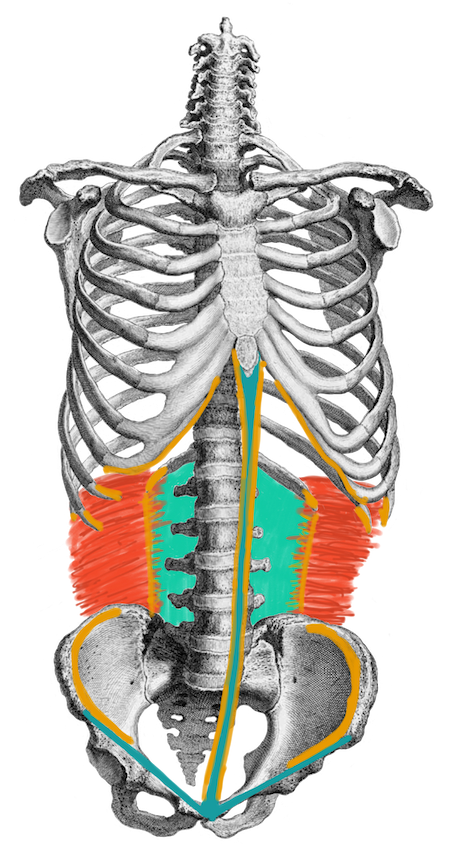

First, let's understand the muscle's location and attachments. We'll start by adding some key connective tissue structures to our skeleton.

- thoracolumbar fascia

- inguinal ligament

- linea alba

-

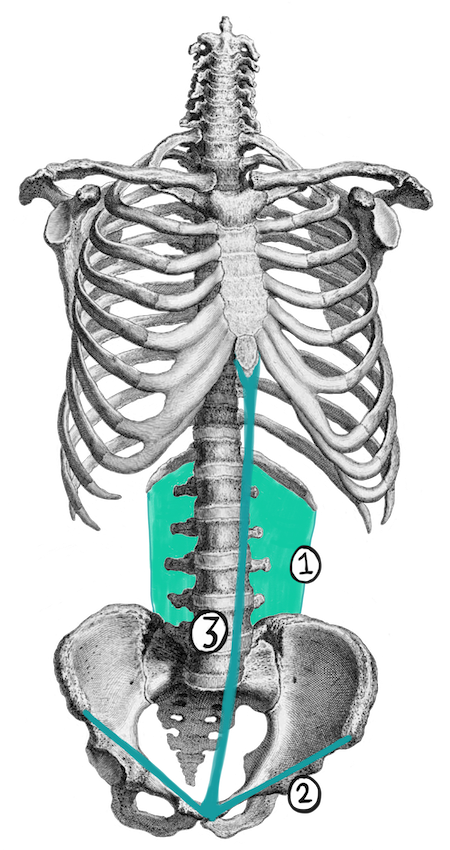

First, let's understand the muscle's location and attachments. We'll start by adding some key connective tissue structures to our skeleton.

- thoracolumbar fascia

- inguinal ligament

- linea alba

The yellow line shows where the muscle attaches.

-

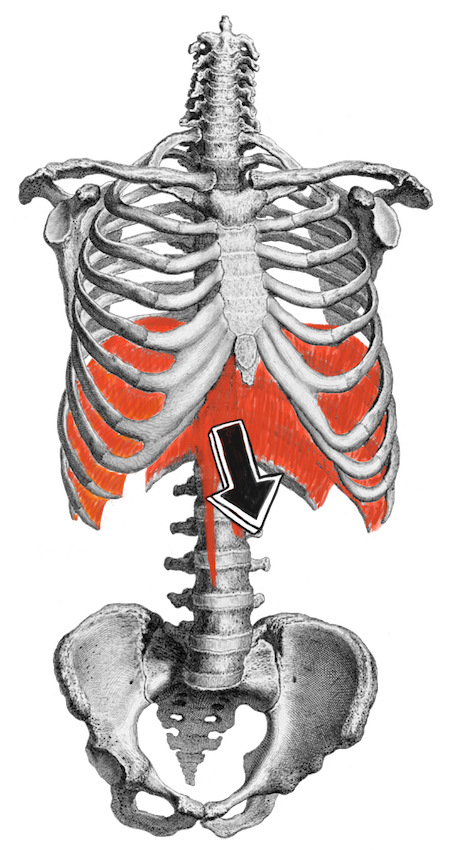

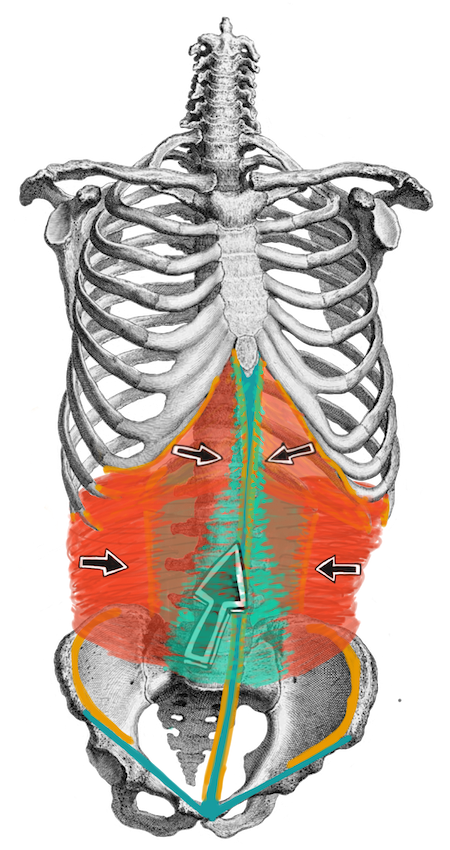

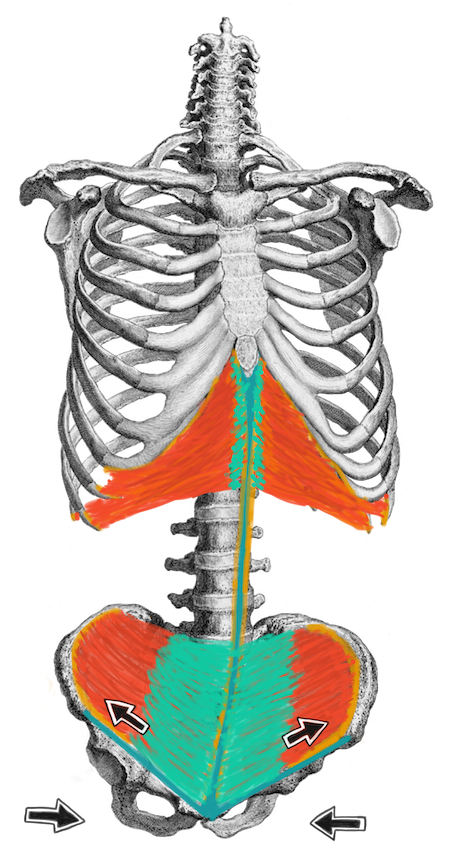

Because of the range of attachment locations, different parts of the muscle serve somewhat different functions.

The middle part attaches to the spine, via the thoracolumbar fascia in the back…

-

Because of the range of attachment locations, different parts of the muscle serve somewhat different functions.

The middle part attaches to the spine, via the thoracolumbar fascia in the back…

…and the linea alba in the front.

The teal that radiates from the linea alba represents what is called an aponeurosis, a sheet of fascia — essentially a flattened tendon.

-

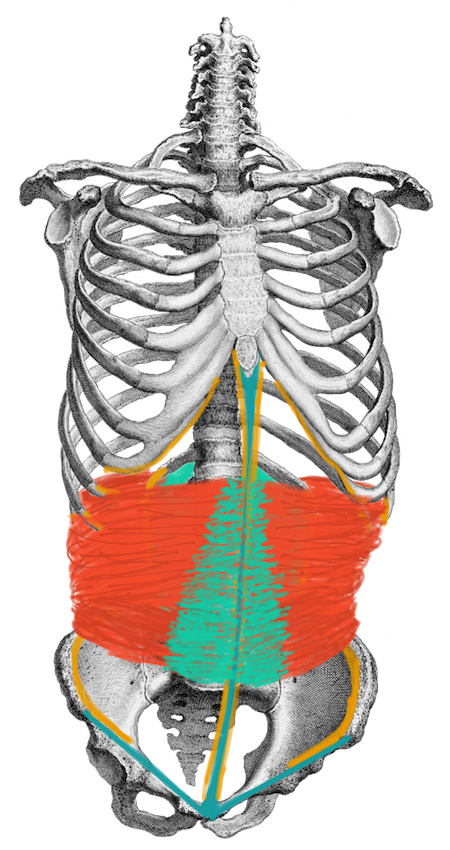

The upper part originates* on the inner surfaces of the lowest six ribs, where it interdigitates with the diaphragm, and inserts into the aponeurosis radiating from the linea alba.

The terms “origination” and “insertion” are used to describe muscle attachment sites. Roughly speaking, “origination” describes the larger structure, while “insertion” is the end that is more likely to be pulled on. In fact, both ends get pulled on and moved. For our purposes, just knowing where the muscle attaches at each end is what's important.

-

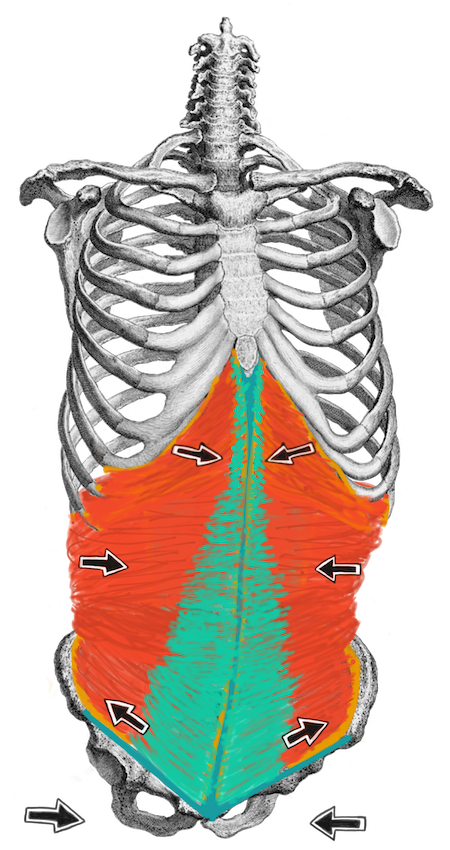

The lower part of the transversus abdominis originates on the iliac crests and the lateral third of the inguinal ligaments, and inserts into the aponeurosis at the midline.

-

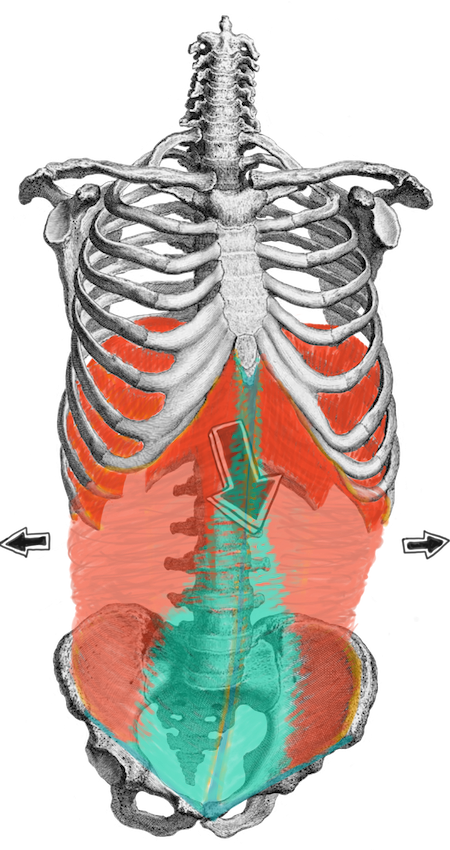

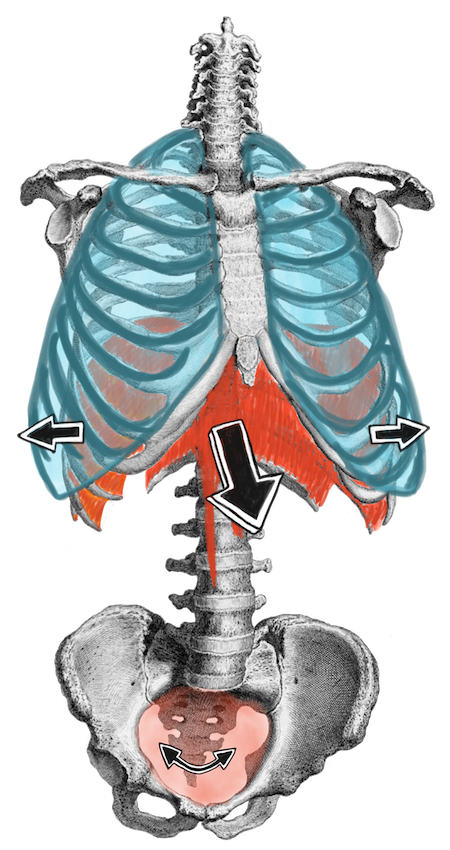

So what happens when we breathe?

If you can inhale deeply without clenching anything, for instance your stomach muscles or your butt, your diaphragm will descend as it contracts, pushing against the abdominal organs. In a deep breath, the organs are moved a lot, as you can clearly see in this real-time video MRI by Biomedizinische NMR Forschungs GmbH.

-

Generally speaking, as the diaphragm pushes against the abdominal organs, they will in turn push against the body wall, and the transversus abdominalis will lengthen.

-

Both your lungs and ribcage will expand. In a deep inhale, the ribcage will expand in all directions, but most noticeably to the sides and front.

-

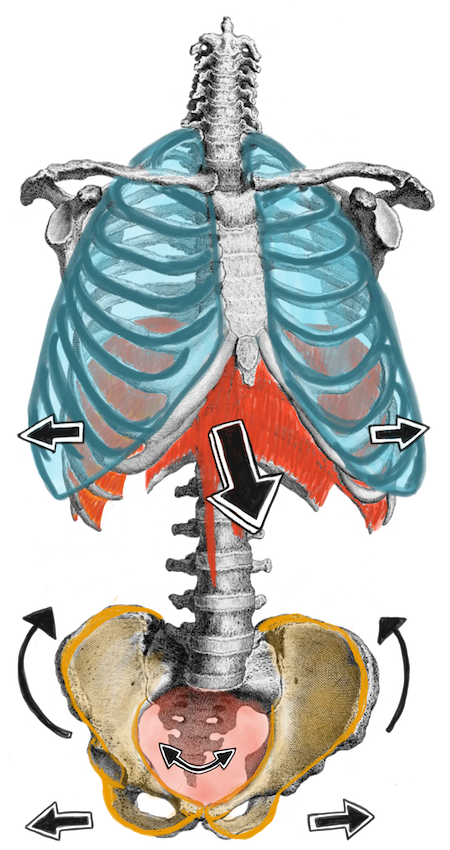

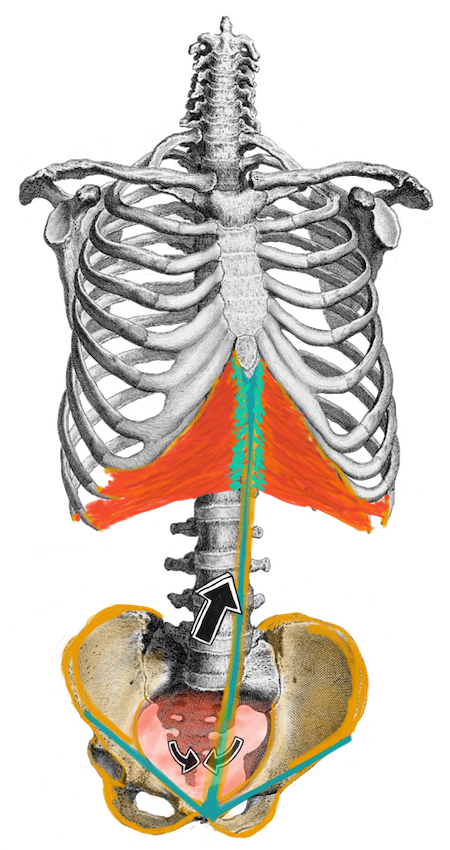

As your organs move downward into the pelvis, you may be able to feel your pelvic floor widen slightly.

Fair warning: This widening can be hard to feel. I often work extensively with students on exercises to help them understand and feel the movements in the pelvis and pelvic floor before they can sense the gentle and subtle movement in the area that comes with breathing.

-

Even the bones of the pelvis will move, widening at the bottom and narrowing at the top. This movement is very subtle, a much smaller version of the movement that occurs when you sit or squat.

If you have one of those big physio balls, try sitting on it while taking some slow, deep, relaxed breaths. See if you can feel your pelvic floor pushing down into the physio ball as you inhale, widening with the inhale, narrowing with the exhale.

-

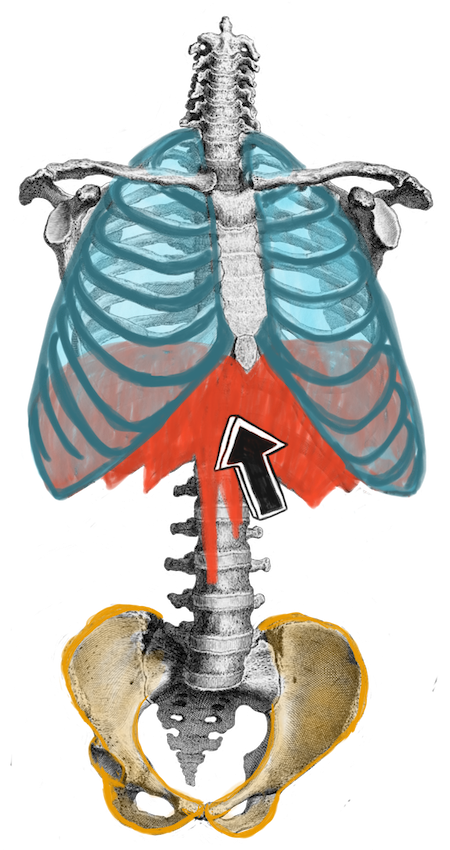

As you exhale, your diaphragm starts to ascend, and your ribcage starts to return to its neutral, before-inhalation position.

-

In fact, the bones and cartilages of your ribcage are very elastic. This means that the movement energy you put into expanding your ribcage during the inhale is now stored in the form of elastic energy, much in the way of a rubber band that has been stretched taut. If you release your breath quickly, as in a sigh, you will use this elastic energy to exhale a good portion of your breath without having to exert any perceivable muscular effort.

Thanks, elasticity!

-

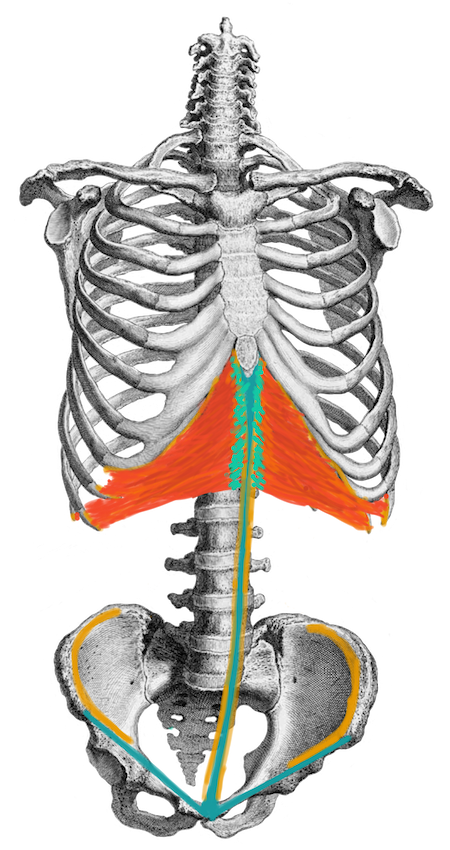

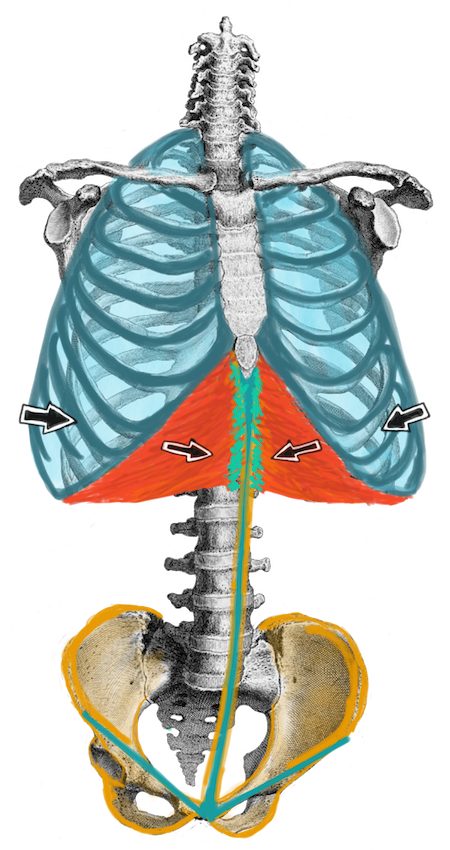

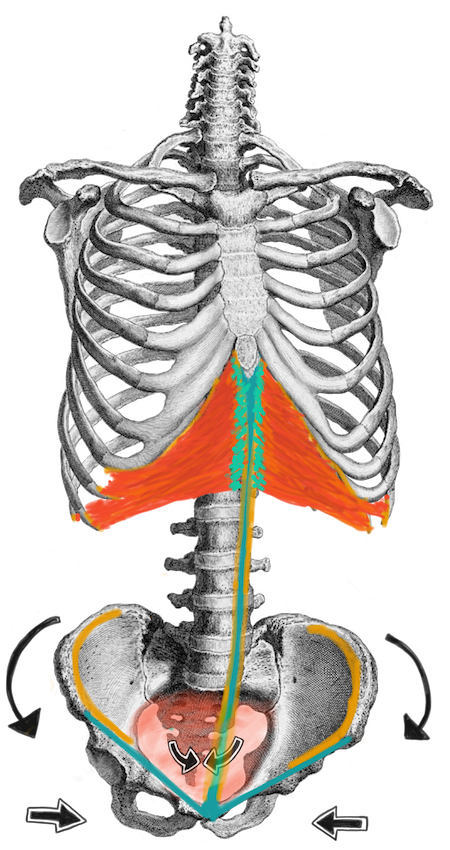

When we're singing, the return of the ribcage to its before-inhale neutral position is slowed through the dynamic, inter-related actions of many different muscles.

The upper part of the transversus abdominis is just one player in this system, helping pull the rib angles (the inverted-V shape formed by the front the the ribcage*) toward one another.

*This area, under the upper part of the transversus abdominis is sometimes referred to as the epigastrium.

-

Your organs can also store elastic energy. Once they are not being pushed down by the diaphragm, they will rebound, helping push the diaphragm up.

The middle part of the transversus abdominis will shorten to help move the organs back into place…

-

Your organs can also store elastic energy. Once they are not being pushed down by the diaphragm, they will rebound, helping push the diaphragm up.

The middle part of the transversus abdominis will shorten to help move the organs back into place…

…aided by a shortening contraction in the muscles of the pelvic floor.

-

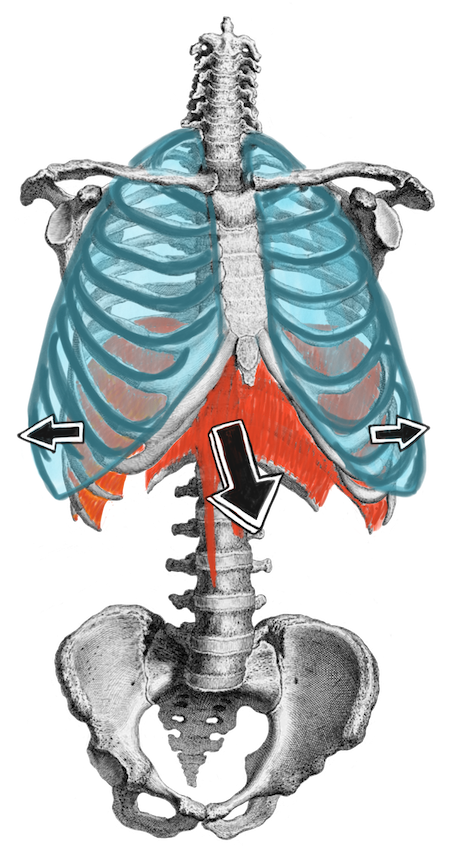

The sit bones, at the base of your pelvis, move together, while the upper halves of the pelvis, the ilia, flare apart.

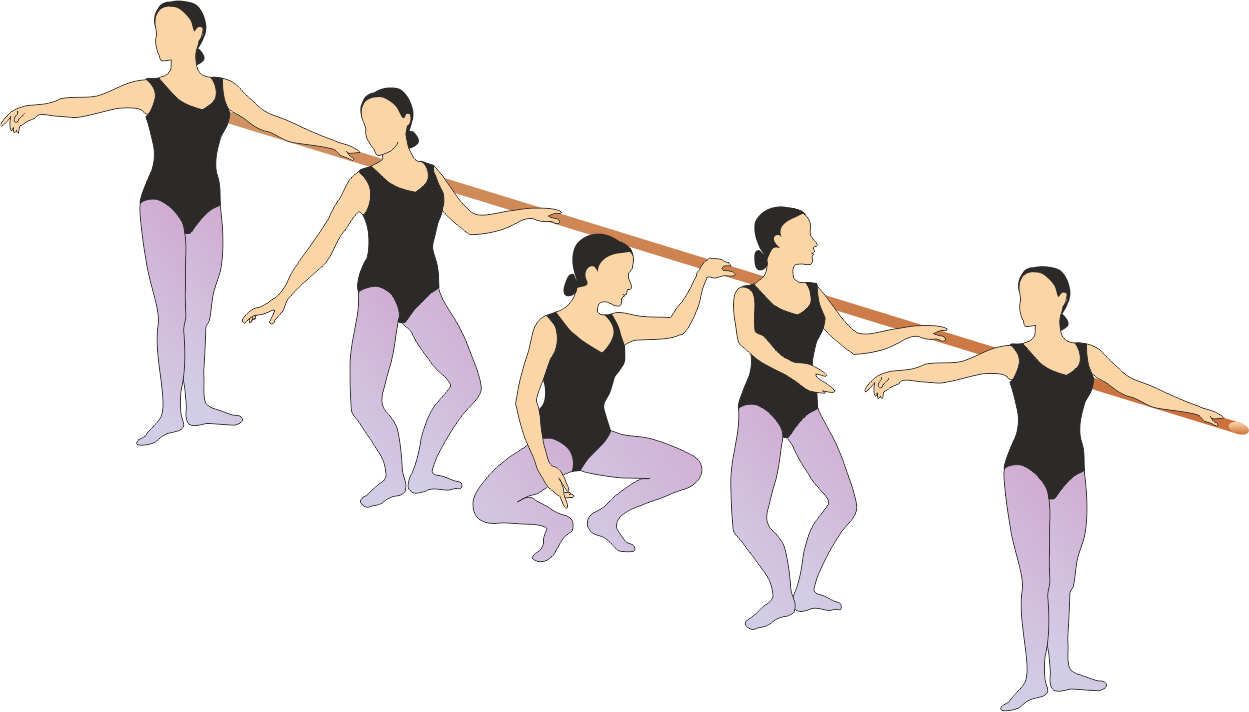

Once again, this is a very subtle movement to feel just from breathing. To better understand the movement, it can help to make it bigger, for instance by doing a plié or squat.

-

Try putting your arms behind you and touching your sit bones. As you lower into the plié, your sit bones will move to the sides, widening your pelvic floor. As you come up, they will move together.

Do this a few times, then try sitting, upright on your sit bones, and breathing deeply. Imagine the sit bones moving apart on the inhale, together on the exhale.

Illustration by Heli Santavouri. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

-

Another way to feel this movement of the bones of the pelvis is to touch your anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS). These are the bony prominences in the front of the pelvis that people often refer to as their "hip bones".

Try a few pliés while touching these points. As you go down, they will flare inward slightly. As you come back up, they'll move apart. This is the same movement pattern we're going to try and tune in to with breathing: Inflare with inhale; widening with exhale.

-

If the anterior-superior iliac spines are inflaring with the inhale and outflaring with the exhale, what does that mean for the lower part of the transversus abdominis, which connects upper halves of the pelvis (the ilia) via the linea alba?

It's lengthening on the exhale.It's lengthening while we're singing.

-

On the exhale, as the upper and middle parts of the muscle are shortening, the lower part is lengthening. The muscle is acting as its own antagonist.

What makes this a useful meditation and embodiment for the singer? Here are a couple of biggies:

- Many singers have a tendency to clench around the exhale, over-muscling in a way that creates a “pressed” or “forced” tone. Working with a sense of widening and expansion in the lower abdomen is a great way to counter this habit.

- Adding an awareness of the lower part of the transversus abdominis helps expand the singer's engagement with the body downward, another tool for learning to sing with the whole body.